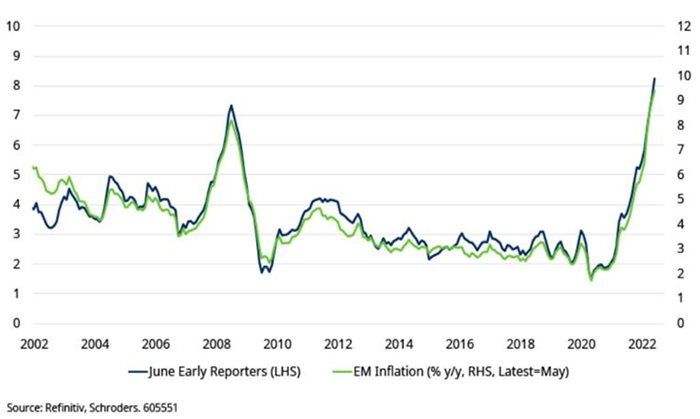

Inflation in emerging markets (EM) appears to have climbed further in June. Concerns that we’ve not yet seen “peak inflation” may add to pressure on EM assets. This is at a time when EM are already under pressure as investors increasingly price in a global recession.

Inflation has been generally higher than expected in the 13 major EMs to have published data in the past week. On the basis of these “early reporters”, broad EM inflation seems to have climbed even further from the two-decade high 9% rate (year-on-year, or y/y) registered in May.

We’re ignoring Turkey in this analysis given the specific challenges of a slow-motion balance of payments crisis, which drove consumer prices index (CPI) growth to 80% y/y in June.

Data released today showed that consumer price inflation in South Africa climbed to a 13-year high of 7.4% y/y in June, from 6.5% y/y in May. The June reading was higher than expected – the consensus of forecasters was for the CPI rate to be 7.2% last month – and due to broad price pressures. Food, energy and core inflation all rose further.

We came into 2022 looking for a peak in EM inflation to be the catalyst for opportunities in local bond markets. We anticipated this as food and energy inflation rolled over, and past interest rate hikes curbed demand pressures.

That view was overtaken by twin exogenous shocks earlier this year that caused EM inflation to take another leg up and bond markets to further sell off.

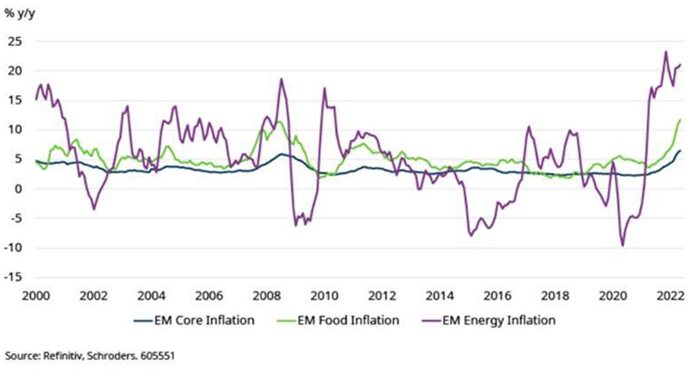

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February spurred sharp increases in food and energy commodity prices. Meanwhile, the introduction of lockdowns in China to contain outbreaks of Covid-19 saw some renewed disruption to global supply chains that added to core inflation pressures.

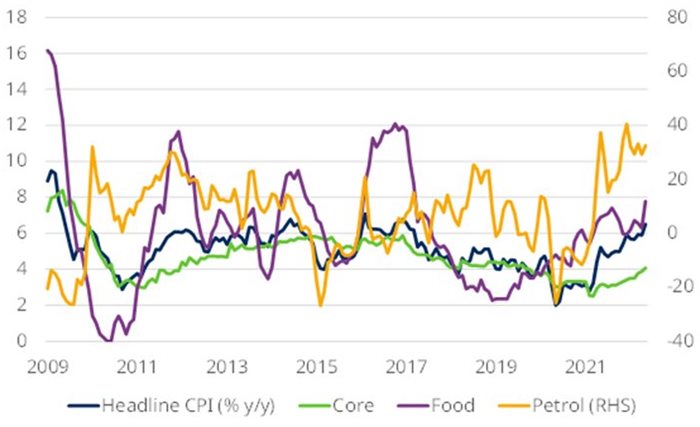

Looking ahead, there are diverging risks when it comes to the outlook for food and energy inflation. For example, projections based on futures prices indicate that items such as petrol inflation should start to come off quite sharply in the second half of the year.

The obvious risk is that oil prices take another leg up. However, there appear to still be upside risks to food inflation, which has been creeping higher over the past couple of years.

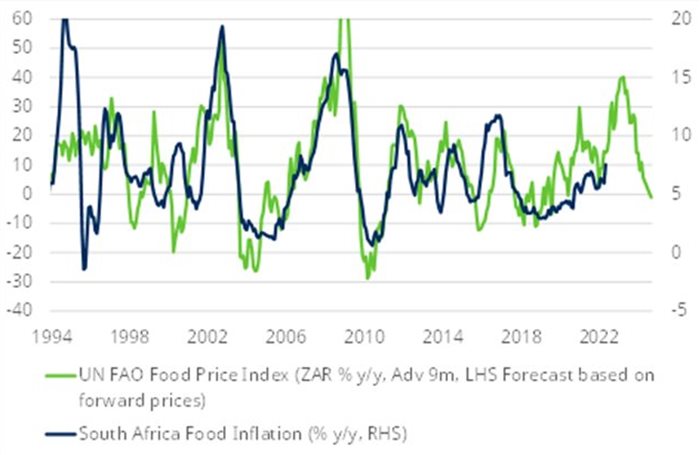

The relationship between food prices and local food inflation is not as strong as it was in the past, but there is a clear risk that food inflation will rise further.

Energy markets are particularly vulnerable amid concerns that Russia will cut off gas supplies to Europe. Meanwhile, disruption to fertiliser supplies threaten agricultural prices, along with climate change and country-level export bans of some foodstuffs.

Beyond these idiosyncratic risks, though, the macroeconomic drivers of commodities have deteriorated. Incoming activity indicators have softened and the risk of a global recession is rising.

This has begun to put downward pressure on the prices of many commodities in recent weeks and the potential for demand destruction suggests there is still more downside.

At the very least, barring a much more aggressive stimulus in China, it seems unlikely that demand pressures will drive commodity prices significantly higher.

This implies that EM food and energy inflation should fall in the months ahead. Admittedly, using forward-pricing for inflation has been a fool’s errand in the past couple of years. The backwardation of futures pricing has been consistently wrong and one reason why many economists have mis-read the inflation outlook.

However, the current pricing of lower commodity prices is at least now aligned with a deteriorating growth outlook and implies that inflationary pressures should ease. Indeed, as the two charts below show, taken at face value food and energy inflation could fall by 6 and 20 percentage points (pps) respectively over the next year. That would be enough to knock around 2.5pps off average EM headline inflation.

From the commodities perspective in South Africa, there are diverging risks when it comes to the outlook for food and energy inflation. For example, projections based on futures prices indicate that items such as petrol inflation should start to come off quite sharply in the second half of the year.

The obvious risk is that oil prices take another leg up. However, there appear to still be upside risks to food inflation, which has been creeping higher over the past couple of years. The relationship between food prices and local food inflation is not as strong as it was in the past, but there is a clear risk that food inflation will rise further.

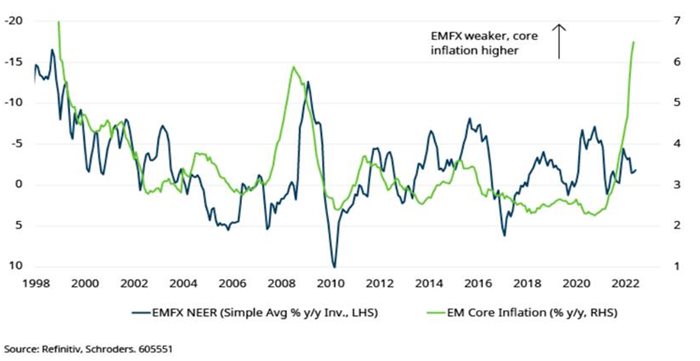

Rising core inflation has been a global phenomenon and reopening frictions and disruption to global supply chains have boosted goods prices. So long as core inflation is overshooting, central banks around the world will be under pressure to lift interest rates more quickly.

But whereas there are concerns about wage-price spirals in some economies around the world, this should not be an issue given structurally high unemployment in South Africa. Tighter policy and spare capacity ought to also eventually weigh on core inflation.

EM core inflation should benefit from an easing of shortages of goods in the months ahead. Global purchasing managers indices (PMIs) show that supplier delivery times are improving as inventories are rebuilt, while port activity in China appears to be normalising.

A more general rotation of global demand towards services should also help to take the sting out of goods inflation.

However, EM core inflation has overshot many indicators of price pressures. For example, core inflation is much higher than the rate implied by producer prices, which themselves have risen further than companies’ output prices. Plus the relationship between underlying inflation and exchange rate movements has completely broken down.

This suggests that disruption to the goods sector has not been the only driver of higher inflation and that overheating economies have also pushed up prices in some instances.

There are of course nuances at the country level, but in general this means EM central banks need to get policy rates significantly into positive territory in order to dampen demand pressures.

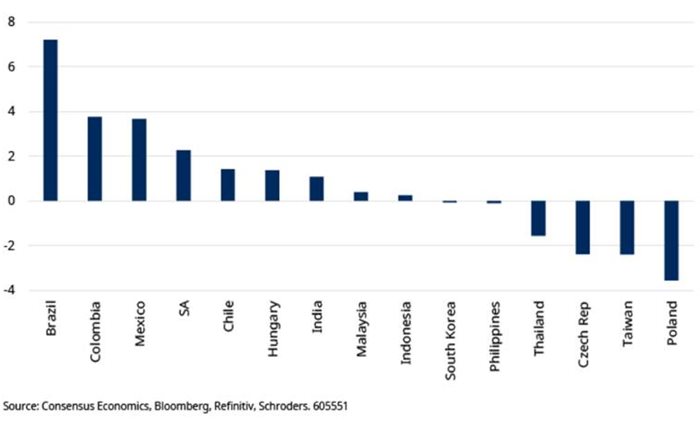

By comparing expectations for inflation over the next year to what is priced into markets for EM policy rates, it becomes clear that central banks in Latin America are on track to achieve this. Indeed, real rates in the region may start to look prohibitive as the economic outlook deteriorates, suggesting that there are opportunities in these markets.

At the other end of the scale, though, expected real policy rates look too low in parts of Eastern Europe and Asia meaning that these bond markets are vulnerable to a further repricing.

1 Year Ahead Market-Implied Policy Rate -

1 Year Ahead Rolling Consensus Inflation Forecast